This transcript has been edited for clarity.

F. Perry Wilson, MD, MSCE

F. Perry Wilson, MD, MSCE: I am joined today by Dr Ohad Einav. He's a staff surgeon in orthopedics at Hadassah Medical Center in Jerusalem. He's with me to talk about an absolutely incredible surgical case, something that is terrifying to most non–orthopedic surgeons and I imagine is fairly scary for spine surgeons like him as well. It's a case of internal decapitation that has generated a lot of news around the world because it happened to a young boy. But what we don't have is information about how this works from a medical perspective. So, first of all, Dr Einav, thank you for taking time to speak with me today.

Ohad Einav, MD

Ohad Einav, MD: Thank you for having me.

Wilson: Can you tell us about Suleiman Hassan and what happened to him before he came into your care?

Einav: Hassan is a 12-year-old child who was riding his bicycle on the West Bank, about 40 minutes from here. Unfortunately, he was involved in a motor vehicle accident and he suffered injuries to his abdomen and cervical spine. He was transported to our service by helicopter from the scene of the accident.

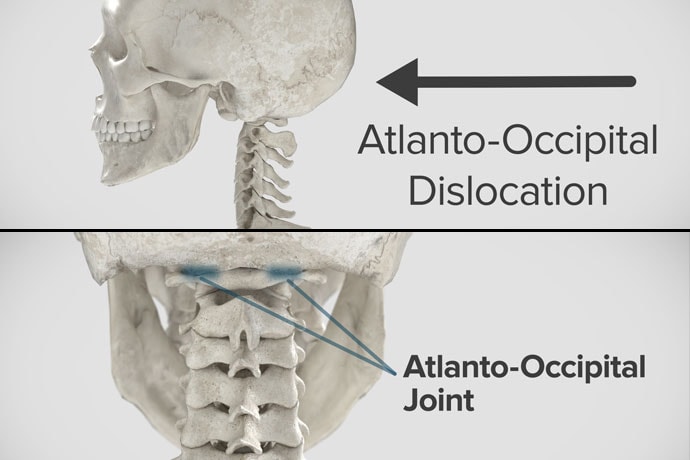

Wilson: "Injury to the cervical spine" might be something of an understatement. He had what's called atlanto-occipital dislocation, colloquially often referred to as internal decapitation. Can you tell us what that means? It sounds terrifying.

Einav: It's an injury to the ligaments between the occiput and the upper cervical spine, with or without bony fracture. The atlanto-occipital joint is formed by the superior articular facet of the atlas and the occipital condyle, stabilized by an articular capsule between the head and neck, and is supported by various ligaments around it that stabilize the joint and allow joint movements, including flexion, extension, and some rotation in the lower levels.

Wilson: This joint has several degrees of freedom, which means it needs a lot of support. With this type of injury, where essentially you have severing of the ligaments, is it usually survivable? How dangerous is this?

Einav: The mortality rate is 50%-60%, depending on the primary impact, the injury, transportation later on, and then the surgery and surgical management.

Wilson: Tell us a bit about this patient's status when he came to your medical center. I assume he was in bad shape.

Einav: Hassan arrived at our medical center with a Glasgow Coma Scale score of 15. He was fully conscious. He was hemodynamically stable except for a bad laceration on his abdomen. He had a Philadelphia collar around his neck. He was transported by chopper because the paramedics suspected that he had a cervical spine injury and decided to bring him to a Level 1 trauma center.

He was monitored and we treated him according to the ACLS [advanced cardiac life support] protocol. He didn't have any gross sensory deficits, but he was a little confused about the whole situation and the accident. Therefore, we could do a general examination but we couldn't rely on that regarding any sensory deficit that he may or may not have. We decided as a team that it would be better to slow down and control the situation. We decided not to operate on him immediately. We basically stabilized him and made sure that he didn't have any traumatic internal organ damage. Later on we took him to the OR and performed surgery.

Wilson: It's amazing that he had intact motor function, considering the extent of his injury. The spinal cord was spared somewhat during the injury. There must have been a moment when you realized that this kid, who was conscious and could move all four extremities, had a very severe neck injury. Was that due to a CT scan or physical exam? And what was your feeling when you saw that he had atlanto-occipital dislocation?

Einav: As a surgeon, you have a gut feeling in regard to the general examination of the patient. But I never rely on gut feelings. On the CT, I understood exactly what he had, what we needed to do, and the timeframe.

Wilson: You've done these types of surgeries before, right? Obviously, no one has done a lot of them because this isn't very common. But you knew what to do. Did you have a plan? Where does your experience come into play in a situation like this?

Einav: I graduated from the spine program of Toronto University, where I did a fellowship in trauma of the spine and complex spine surgery. I had very good teachers, and during my fellowship I treated a few cases in older patients that were similar but not the same. Therefore, I knew exactly what needed to be done.

Wilson: For those of us who aren't surgeons, take us into the OR with you. This is obviously an incredibly delicate procedure. You are high up in the spinal cord at the base of the brain. The slightest mistake could have devastating consequences. What are the key elements of this procedure? What can go wrong here? What is the number-one thing you have to look out for when you're trying to fix an internal decapitation?

Einav: The key element in surgeries of the cervical spine — trauma and complex spine surgery — is planning. I never go to the OR without knowing what I'm going to do. I have a few plans — plan A, plan B, plan C — in case something fails. So, I definitely know what the next step will be. I always think about the surgery a few hours before, if I have time to prepare.

The second thing that is very important is teamwork. The team needs to be coordinated. Everybody needs to know what their job is. With these types of injuries, it's not the time for rookies. If you are new, please stand back and let the more experienced people do that job. I'm talking about surgeons, nurses, anesthesiologists — everyone.

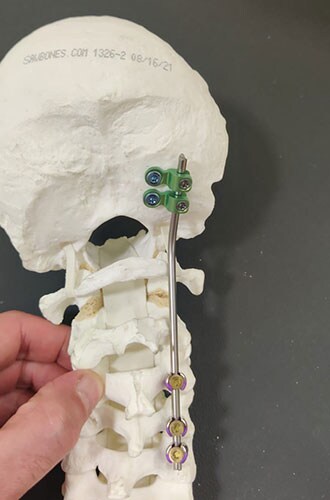

Another important thing in planning is choosing the right hardware. For example, in this case we had a problem because most of the hardware is designed for adults, and we had to improvise because there isn't a lot of hardware on the market for the pediatric population. The adult plates and screws are too big, so we had to improvise.

Wilson: Tell us more about that. How do you improvise spinal hardware for a 12-year-old?

Einav: In this case, I chose to use hardware from one of the companies that works with us. I can show you.

You can see in this model the area of the injury, and the area that we worked on. To perform the surgery, I had to use some plates and rods from a different company. This company's (NuVasive) hardware has a small attachment to the skull, which was helpful for affixing the skull to the cervical spine, instead of using a big plate that would sit at the base of the skull and would not be very good for him. Most of the hardware is made for adults and not for kids.

Wilson: Will that hardware preserve the motor function of his neck? Will he be able to turn his head and extend and flex it?

Einav: The injury leads to instability and destruction of both articulations between the head and neck. Therefore, those articulations won't be able to function the same way in the future. There is a decrease of something like 50% of the flexion and extension of Hassan's cervical spine. Therefore, I decided that in this case, there would be no chance of saving Hassan's motor function unless we performed a fusion between the head and the neck, and therefore I decided that this would be the best procedure with the best survival rate. So, in the future, he will have some diminished flexion, extension, and rotation of his head.

Wilson: How long did his surgery take?

Einav: To be honest, I don't remember. But I can tell you that it took us time. It was very challenging to coordinate with everyone. The most problematic part of the surgery to perform is what we call "flip-over."

The anesthesiologist intubated the patient when he was supine, and later on, we flipped him prone to operate on the spine. This maneuver can actually lead to injury by itself, and injury at this level is fatal. So, we took our time and got Hassan into the OR. The anesthesiologist did a great job with the GlideScope — inserting the endotracheal tube. Later on, we neuromonitored him. Basically, we connected Hassan's peripheral nerves to a computer and monitored his motor function. Gently we flipped him over, and after that we saw a little change in his motor function, so we had to modify his position so we could preserve his motor function. We then started the procedure, which took a few hours. I don't know exactly how many.

Wilson: That just speaks to how delicate this is for everything from the intubation, where typically you're manipulating the head, to the repositioning. Clearly this requires a lot of teamwork.

What happened after the operation? How is he doing?

Einav: After the operation, Hassan had a great recovery. He's doing well. He doesn't have any motor or sensory deficits. He's able to ambulate without any aid. He had no signs of infection, which can happen after a car accident, neither from his abdominal wound nor from the occipital cervical surgery. He feels well. We saw him in the clinic. We removed his collar. We monitored him at the clinic. He looked amazing.

Wilson: That's incredible. Are there long-term risks for him that you need to be looking out for?

Einav: Yes, and that's the reason that we are monitoring him post-surgery. While he was in the hospital, we monitored his motor and sensory functions, as well as his wound healing. Later on, in the clinic, for a few weeks after surgery we monitored for any failure of the hardware and bone graft. We check for healing of the bone graft and bone substitutes we put in to heal those bones.

Wilson: He will grow, right? He's only 12, so he still has some years of growth in him. Is he going to need more surgery or any kind of hardware upgrade?

Einav: I hope not. In my surgeries, I never rely on the hardware for long durations. If I decide to do, for example, fusion, I rely on the hardware for a certain amount of time. And then I plan that the biology will do the work. If I plan for fusion, I put bone grafts in the preferred area for a fusion. Then if the hardware fails, I wouldn't need to take out the hardware, and there would be no change in the condition of the patient.

Wilson: What an incredible story. It's clear that you and your team kept your cool despite a very high-acuity situation with a ton of risk. What a tremendous outcome that this boy is not only alive but fully functional. So, congratulations to you and your team. That was very strong work.

Einav: Thank you very much. I would like to thank our team. We have to remember that the surgeon is not standing alone in the war. Hassan's story is a success story of a very big group of people from various backgrounds and religions. They work day and night to help people and save lives. To the paramedics, the physiologists, the traumatologists, the pediatricians, the nurses, the physiotherapists, and obviously the surgeons, a big thank you. His story is our success story.

From left to right: Dr Ziv Asa, Suleiman Hassan, and Dr Ohad Einav.

Wilson: It's inspiring to see so many people come together to do what we all are here for, which is to fight against suffering, disease, and death. Thank you for keeping up that fight. And thank you for joining me here on Medscape.

Einav: Thank you very much.

Follow Medscape on Facebook, X (formerly known as Twitter ), Instagram, and YouTube

Credits:

Image 1: Anthony Decarlo/Yale School of Medicine

Image 2: Medscape/Turbosquid

Image 3: Hadassah Medical Center

Image 4: Medscape/Turbosquid

Image 5: Medscape/Turbosquid

Image 6: Hadassah Medical Center

Image 7: Hadassah Medical Center

Medscape Pediatrics © 2023

Cite this: 'Decapitated' Boy Saved by Surgery Team - Medscape - Sep 01, 2023.

Comments